A new independent report from The Office of Health Economics (OHE), and Professor Alistair McGuire of the London School of Economics (LSE), has underlined the potential financial risk to the NHS of the increasing VPAS rebate rate on branded generics and biosimilars, a move that could lead to market withdrawals of these medicines.

The OHE analysis shows that the rising VPAS rebate rate - which is estimated to increase to 23.7% next year, but could be even higher than 30% - is having a significant negative impact on branded generic and biosimilar manufacturers.

In particular, the study looked at what the impact would be on NHS medicines costs over the lifetime of the next VPAS, from 2024-2028 inclusive. Looking at a range of indicative rebate levels, the study compared what the Government is projected to receive in revenue from a sales levy on branded generics and biosimilars over that five-year period with what NHS savings are in jeopardy from reduced generic and biosimilar competition.

The competitive nature of the market these products already operate in typically reduces cost by up to 80% or even more in many cases, compared to the price of the originator version when it was patent protected. The addition of the elevated VPAS rebate rate on top means supplying these products can quickly become economically unviable.

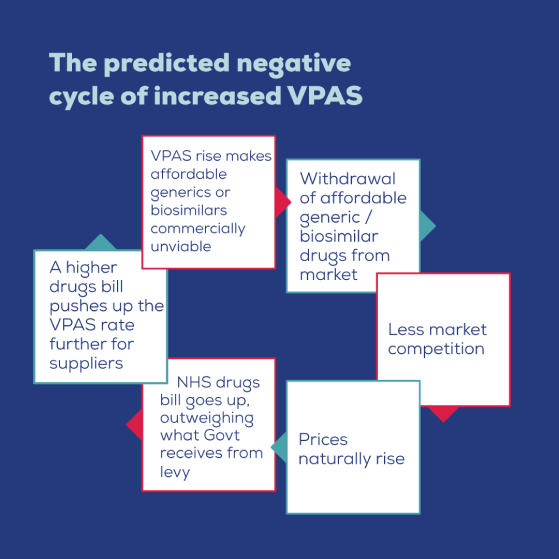

As a result, competition - which is the bedrock of the value delivered by both the branded generic and biosimilar sectors - risks being seriously eroded. This means that the NHS is forecast to lose out on billions of pounds of savings every year, over and above any revenue the scheme is designed to recoup.

VPAS FAQs

What is VPAS?

The Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS) is an agreement between the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHS England, the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI). BGMA, which represents manufacturers who supply 80% of the medicines used in the NHS, and whose membership includes 8 out the top 10 largest suppliers to the NHS by volume, were not included in the negotiations.

The scheme covers medicines that are marketed with a brand name. In addition to the drugs that originator companies sell – those who invent and patent medicines – the scheme also includes manufacturers and suppliers of branded generic and biosimilar medicines. The originator company’s patent or period of exclusivity is no longer in force covering these medicines, which enables more manufacturers to enter the market and supply their own versions.

How does it work and what is the rebate?

VPAS contains an annual repayment rebate which branded medicines manufacturers have to pay. The repayment percentage for each year of VPAS depends on the difference between the allowed annual growth of 2% and the actual growth in sales to the NHS of the branded medicines. For example, in 2019, the first calendar year of VPAS, the repayment percentage was 9.6%, and in total, pharmaceutical companies repaid DHSC just under £850 million.

The rate was most recently raised from 5.1% in 2021 to 15% covering this year. This appears to be the result of the NHS spending proportionally more on high-cost innovator medicines and the focus on Covid-19 meaning that lower levels of switching to cost-effective treatments took place.

Next year it is expected to rise to 23.7%, however recent 2022 medicines growth figures suggest that the 2023 rate could be even higher than 30%. The current agreement then renews in 2024. The scale of the levy is exacerbated by manufacturers of blockbuster patented (new active substance) medicines being exempted for three years, the costs of which other VPAS member companies have to bear.

How does it impact the generic medicines market?

Branded medicines which fall under the remit of the scheme make up about 30% of all prescription medicines in England. Of those about a third are branded generics and biosimilars.

Biosimilar medicines and many branded generics are branded because it is a requirement of the regulator the MHRA in patients’ interests. For example, the regulator states that patients of certain treatments should be maintained on a single manufacturer's brand. Yet doctors often nonetheless prescribe generically to enable competition, or the most affordable versions are procured through competitive tenders. So, the brand may not necessarily offer any particular value but does mean that these products must be included within VPAS or the similar statutory scheme which operates in a comparable fashion.

Branded generics and biosimilars by dint of being genericised already mean they face competition when they enter the market which drives down prices. For example, research shows that the average branded generic is a third of the price of the originator pre-loss of exclusivity, with around one third of those branded generics over 80% less than the originator version. Overall, the system of generic and biosimilar competition delivers annual savings to the NHS of around £15billion and means the UK benefits from the lowest medicine prices in Europe.

This seems potentially unfair?

Branded generics and biosimilars already face competition that drives down the price paid by the NHS, making this VPAS rebate an additional cost burden they are less well-equipped to shoulder than other branded medicines. With the VPAS levy rising rapidly, this is making the supply of some medicines economically unsustainable. A new five year VPAS that continues this approach will make many more treatments economically unsustainable. Analysis conducted by the Office of Health Economics (OHE) supported by Professor McGuire of the London School of Economics (LSE) showed that rather than controlling costs for the NHS, the scheme could be set to cost billions of pounds in forfeited savings every year due to the growth of the annual levy and its detrimental impact on competition.

How big is the potential scale of the problem?

According to research done by OHE, the rising VPAS rebate will force manufacturers to pull out of the market meaning prices will rise due to a lack of competition. Competition is the central mechanism for keeping medicine prices low where there are a number of manufacturers supplying community pharmacies or NHS hospitals with a particular drug. As a result, critical savings to the NHS will be lost. OHE’s forecast analysis looks ahead to the next five-year VPAS period between 2024 and 2028 and shows that at a VPAS rebate rate of 5% the NHS will lose out on £3.071bn of branded generic savings between 2024 and 2028, compared to exempting branded generics and biosimilars from the VPAS levy. This is over and above the projected income (£325m) that the Government would receive for taxing the sale of branded generics and biosimilars to the NHS.

Similarly, taking into account projected levy income, the additional costs to the NHS rise to £3.068bn at 20%, £7.852bn at 25% and £7.811bn at 30%. These lost savings are the consolidation of three costs borne by the NHS: higher reimbursement prices paid for medicines; a reduction in the level of discounts received by local NHS trusts; and higher prices paid for biosimilars in hospital tenders.

Based on the first year of the new VPAS period in 2024 being at a predicted rate of 25%, the NHS is set to lose out by more than £800m of savings in just 12 months as a result of reduced competition.

So, what is the solution?

The British Generic Manufacturers Association (BGMA) is the trade body representing the interests of generic and biosimilar manufacturers. They have argued for a long time that biosimilar medicines and branded generics where it is a regulatory requirement to brand should be exempt from the VPAS rebate as it is in effect a double taxation.

These products already deliver significant savings to the NHS via competition, yet they are also unfairly burdened by this additional punitive levy. The OHE study shows the very harmful impact on the market and ultimately it will be the NHS and patients which are most affected.

The subsidisation of blockbuster drugs by suppliers of far more affordable medicines is just not sustainable. It is time the Government reviewed VPAS to make it fairer and encourage more competition, which has been independently shown to be most effective at regulating the prices of medicines paid by the NHS.