Introduction

The core role of a successful generic medicines manufacturing sector is to get the right medicines at the right time to patients to improve quality of life. This work also stimulates the originator sector to continue research-based activity which results in new and improved medicines for patients.

There are a number of issues, which are important to our members, in which we engage with a range of stakeholders from parliamentary representatives and government departments, through to the European Union.

Generic Pricing

The price paid by the NHS for generic medicines is not that charged by manufacturers but includes distribution costs (which will vary depending on the product type) and the retained margin for community pharmacy (targeted to be £800m per annum).

Typically, the reimbursement price of a generic medicine listed in Category M of the Drug Tariff may amount to approximately twice (or more) the manufacturer’s actual selling price (ASP).

Reports, including those from the OECD; jointly the Institute of Fiscal Studies and the Health Foundation; and The King’s Fund/Nuffield Trust have cited the role of generic medicines in containing the NHS drugs budget and the policies of the Department of Health in increasing generic prescribing and dispensing rates.

Notably, the joint study by the IFS and the Health Foundation reflected that: “In spite of the volume of prescriptions growing by 4.3% per year in England between 2002 and 2012, the total amount spent on community prescriptions remained flat. This is due to a shift away from branded drugs towards generic ones”. This, according to both bodies, has meant that: “in primary care, the cost of prescribing items has fallen over time, though volumes have increased.

The cost per item has fallen from £15 in 2004 to £9 in 2016 in real terms” [a blended branded and generic figure]. The reimbursement price of medicines in Categories A and C are not currently based on actual sales.

The Government will have the powers in 2019 to seek actual sales data on all generic medicines. Whilst the average reimbursement price of a generic medicine has fallen from £5.01 to £4.03 between 2006 and 2017 (NHS Digital) as a result of competition from multiple suppliers, the reimbursement price of branded medicines that do not typically face competition from other manufacturers of the same medicine has increased from £19.71 to £20.73.

Of 620 generic products for which we have consistent data between Q1 2015 and Q2 2018, 161 (26%) showed an increase in reimbursement price over this period and 459 (74%) a decrease. Looking at the quarter of products where prices increased, this may have been necessary to maintain supply in view of increasing costs. In addition, due to companies taking a portfolio approach, the necessary price increases maybe supporting competition and supply on other medicines in the portfolio.

In working to manage the level of retained pharmacy margin at the target of £800m per annum, DHSC changes or recalibrates the reimbursement price of generic medicines in Category M of the Drug Tariff.

The BGMA has analysed the results of generic competition following when originator products (40 products) lost their market exclusivity during the lifetime of the current PPRS. This shows that the actual sales price of generic medicines launched during this period saw an average price reduction of 89% compared with the originator product across the PPRS period, including those launched very close to the end when competition would still be increasing.

Benefits to the NHS

Generic medicines meet the same standards of quality, safety and efficacy as originator brands. It is broadly understood that the significant use of generics within the NHS delivers a range of benefits, including:

Cost containment:

Competition between multiple suppliers of generic medicines rapidly reduces market prices at patent expiry, frequently by more than 90%. Competition between generics and the equivalent original brands also typically reduces the market price of the originator.

Enhanced patient access to treatment:

By reducing the drugs bill to this extent, the use of generics by the NHS (a) allows more patients to be treated with the same product for the same cost; (b) creates “headroom” within the medicines budget to pay for future innovative products and the investment needed to develop them ; and (c) allows the NHS to use the savings elsewhere.

Promotion of innovation:

By providing competition with the originator’s product at expiry of the relevant patents or other exclusivity, generics promote innovation. Without the onset of generic competition, which will significantly reduce the originator’s revenue from the product, there would be much less of an incentive on the originator to develop new products which do not face generic competition.

Enhanced security of supply:

From time to time, all medicines suffer from a shortage of supply due to reasons outside the manufacturer’s control: these typically relate to API or other raw material shortages; manufacturing difficulties, including quality concerns; logistical difficulties; or unexpected demand. For the sole supplier of an exclusive (eg, on patent) product, these difficulties will usually have an immediate effect on the manufacturer’s ability to supply. In the case of a generic product, there will usually be other suppliers of the same medicine which can make up any shortfall.

Whilst the cost of a generic is important in delivering some of these benefits (specifically cost containment and enhanced patient access to treatment), all are increased by the volume or market share of generics, and the development of a competitive multi-source market.

Restrictions in the market share of generics or the number of manufacturers of a particular medicine threaten the continued development of these benefits.

Current supply issues

BGMA supply issues dashboard

Looking at March 2025[1], BGMA provides a monthly snapshot of the numbers of supply issues affecting generic[2] medicines in England, based on UK Government and NHS data. Since our analysis in February 2022, the Department of Health and Social Care has moved its supply issues update to being hosted on the Specialist Pharmacy Service (SPS) website. As a result, we have changed some of the ways we measure different kinds of supply issues to replicate the categorisations in the SPS medicines supply tool.

It is important to note that the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England work with suppliers to resolve and mitigate more supply issues than we count through this analysis. The supply issues we count cover below are the medicine presentations that DHSC and NHSE cannot adequately resolve nor mitigate, or feel it is important to make aware to pharmacists and NHS commissioners.

Supply issues as a proportion of presentations listed in the Drug Tariff[3]

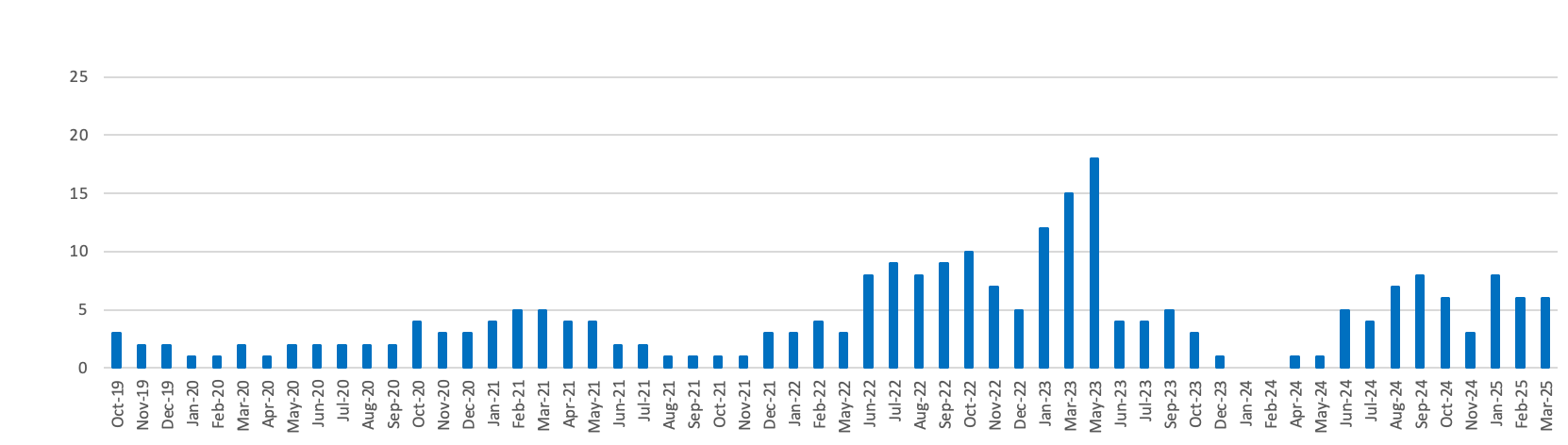

Serious Shortage Protocols currently in place

- Number of generic presentations for which a Serious Shortage Protocol is currently in place = 6

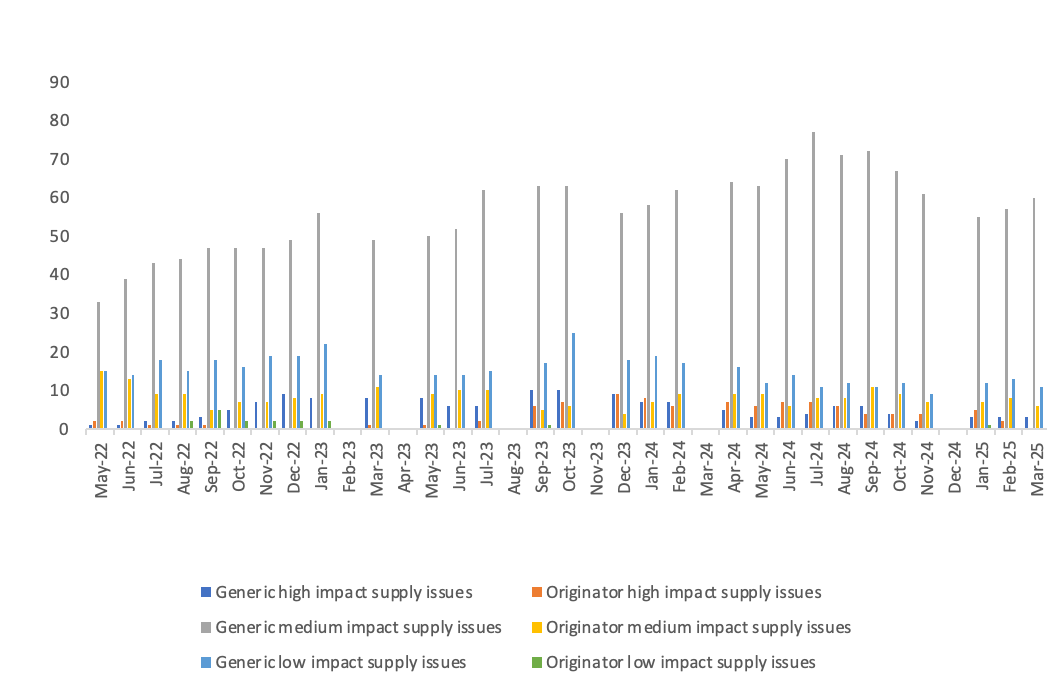

Medicines supply issues measured by Government and the NHS according to their patient impact

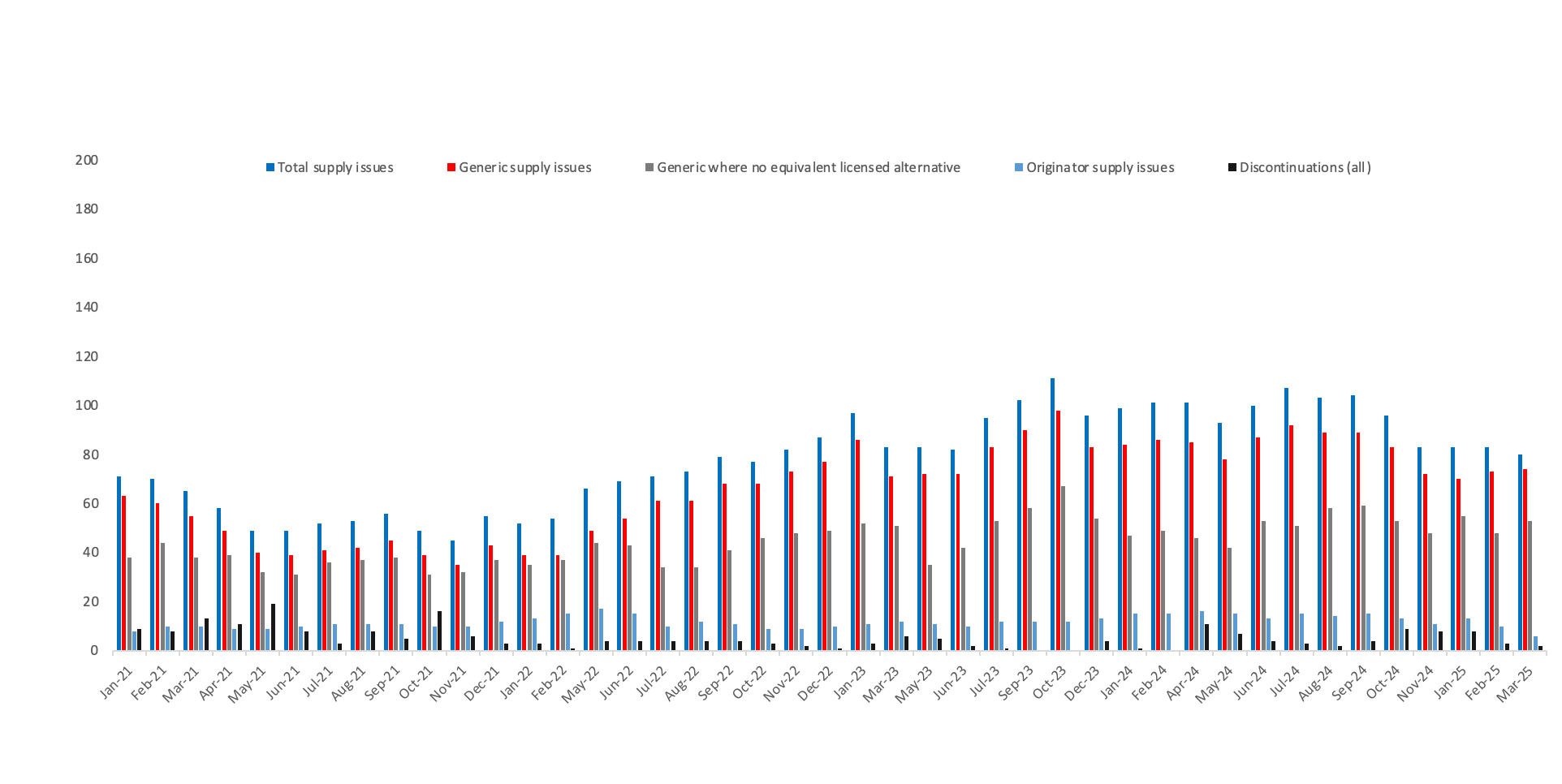

Number of supply issues and discontinuations identified in the SPS medicines supply tool

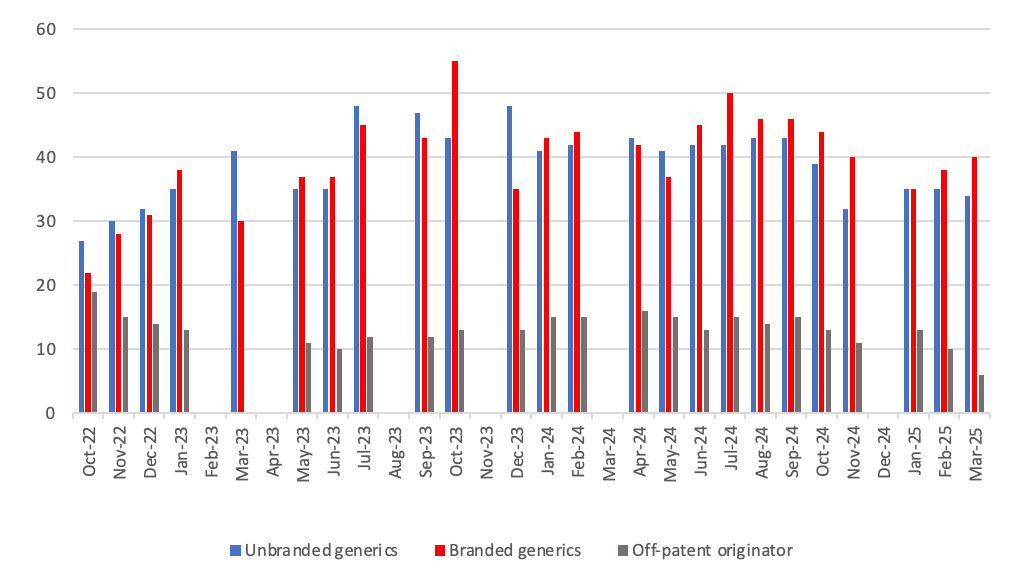

Breakdown of supply issues in off-patent market identified in the SPS medicines supply tool

Notes:

- 1 The BGMA’s analysis of the SPS medicines supply tool was conducted on 12 March 2025.

- 2 In this analysis, we define a generic medicine as a medicine that is not patent protected. As such, we include off-patent originator medicines as generic medicines, since they operate in genercised markets. The dashboard is BGMA’s interpretation of supply issues information issues by the UK Government and NHS. BGMA carries out this analysis categorisation on the basis of what is set out in the notes section.

- 3 Listed under Part VIIIA – the Basic Prices of Drugs. Source: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/pharmacies-gp-practices-and-appliance-contractors/drug-tariff/drug-tariff-part-viii. In March 2025, there were 3,789 different presentations listed in the Drug Tariff. From a sample, we found that 10% of presentations had the same molecule, strength and form as another presentation. We have therefore cut the Drug Tariff measure by 10% to 3,409 to ensure that we are accurately measuring against the supply issues identified in the DHSC supply issues update sheet (explained below), which is compiled on the same molecule, strength and form basis.

- 4 According to the NHS Business Services Authority: “An SSP enables community pharmacists, in the event of a serious shortage of any prescribed item that affects or may affect the whole or any part of the UK, to supply in accordance with the Protocol rather than supply in accordance with a prescription, without going back to the prescriber”. Source: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/pharmacies-gp-practices-and-appliance-contractors/serious-shortage-protocols-ssps

-

5The medicines are categorised by DHSC and the NHS according to impact tiers:

- Low impact: These supply issues are likely to carry low risk and management options and should result in patients being maintained on the same licensed medicine.

- Medium impact: These supply issues will require more intense manage options (such as using therapeutic alternatives, unlicensed imports or alternative strengths or formulations), which may carry a greater risk to patients/health providers than Tier 1 issues, but which are considered safe to be implemented at sub-regional level without further escalation.

- High impact: These supply issues will be more critical, with potential change in clinical practice or patient safety implications that require clinical or operational direction to the system. They will be expected to generate public and clinician concern. The response will be nationally coordinated and guided and the NHS may invoke its Emergency Preparedness Resilience and Response (EPRR) function.

- Critical impact: These supply issues will require additional support from outside the health system and will trigger the use of dedicated national NHS EPRR incident processes and procedures in order to provide additional support for the management of the shortage. Clear links and command and control mechanisms between the Medical Devices and Clinical Consumables Clinical Response Group, NHSE&I Central EU Exit Team, EPRR functions at both NHSE&I and ORC/DHSC, and Cabinet Office will be utilised.

- 6On a rolling basis, DHSC, with the help of the Commercial Medicines Unit covering secondary care, produces and updates a consolidated list of medicines with new, ongoing or resolved supply issues that are being actively managed to prevent or mitigate patient impact. The list is accessible on the SPS medicines supply tool to pharmacists and relevant NHS bodies that prescribe or oversee the prescribing of medicines. The medicines supply tool notes the level of availability of each medicine, providing advice to prescribers where needed. This also includes notice of medicines where the supplier has confirmed that it is discontinuing supply. Regional supply issues may not be captured, such as where other suppliers can fill demand.

- 7We have measured an equivalent licensed alternative as one where a pharmacist can make a switch to another licensed presentation without reverting to the prescriber to change the prescription. This might be where another manufacturer’s product or a different pack size is available, or a parallel import is available. Even where we have listed that there is no equivalent licensed alternative, a different form or strength of the medicine may be available which the patient can be safely prescribed.

- 8Where a generic is licensed and marketed by a brand name, either because it is a regulatory requirement from the medicines regulator, MHRA, or due to a commercial decision to differentiate the product from the supplier.

Patient access

Making medicines more affordable to the NHS and therefore increasing patient access to important, and potentially life-saving, drugs is a key role of the generics industry in the UK. Currently, the NHS is facing major funding challenges due to increased demand from an ageing population, rising cost of new technologies and drugs, as well as the need to increase efficiency through the QIPP agenda.

Generic competition already saves the NHS £13bn a year and allows further investment in new drugs which can support unmet patient need. We firmly believe there is a moral imperative on all of us in the industry, in the supply chain and the Government to ensure that generics are used to the maximum extent as it ultimately unleashes savings which increases patient access to vital medicines.

Patient information

To improve consistent information to patients and significantly reduce the prohibitive cost of each company user-testing every single patient information leaflet (PIL) - at a cost per test in the region of £10,000 - the BGMAS supported co-ordination of user testing of PILs which can be of significant benefit to patients, industry, regulators and the NHS.

The BGMA has worked extensively with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and through an innovative implementation plan we have delivered leadership in improving information to patients about their medicines.

BGMA members also have a strong commitment to ensuring their packaging meets patient needs and compliance and have been congratulated by the previous National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) on leading improvements in this area.

Freedom in market pricing

Generic manufacturers and suppliers have freedom of pricing in the UK, with the Government relying on competition to keep prices low. The Government only intervenes in pricing if competition can be seen not to be working. The very competitive environment in the UK means that manufacturers' ex-factory prices are amongst the lowest in Europe. We believe that they are now so low that some increases will be necessary to create an economically sustainable market for manufacturers and to ensure that they can sustain the investment needed to produce new more complex generics and more costly biosimilar medicines.

Many European countries determine the cost of their generic medicines through centralised tendering and other centralised mechanisms. However, over a number of years, and particularly around 2002, the BGMA has worked with UK government to ensure that this has not become the case in the UK. The Association continues to make the case against centralised tendering in primary care. Our competitive system has led to a vibrant multi-source market, minimising the scope for shortages and delivering the lowest market prices in Europe.

The following reports review the generic medicines market in the UK and its contribution to reducing NHS costs.

OECD - Health at a Glance: Europe 2016 - How does the United Kingdom compare?

In 2016, the OECD published a report (Health at a Glance: Europe 2016) which stated that the development of generic medicines markets across Europe has provided a good opportunity to increase efficiency in pharmaceutical spending. It stated that generics accounted for 84% of the volume of pharmaceuticals sold in the UK in 2014 - the highest among EU countries - but that this represented only around a third of the total market value. The OECD’s specific UK findings can be found here.

NERA - Manufacture, distribution and reimbursement of generic medicines in the UK

A 2001 report conducted by economic consultancy NERA into the manufacture, distribution and reimbursement of generic medicines in the UK reviewed the effectiveness of the freedom of pricing system, as well as alternative pricing and reimbursement systems. NERA’s analysis highlighted the benefits of a reimbursement system based on market prices (not list prices) fixed by competition in preference to other alternatives such as tendering, reference pricing, profit controls or direct price controls. Following the report, the Department of Health implemented a reimbursement system based on market prices – which helped realise more savings for the taxpayer and supported widened patient access to medicines. The report can be found here.

Getting to market

When a drug becomes off-patent, competition from generic manufacturers is a very efficient way of driving down prices and increasing savings potential for the NHS as well as delivering innovation through offering competition to patent expired brands. However, there can be a number of barriers which prevent generic competition. As an industry, we face risks to our ability to launch at patent expiry due to activities of the originator sector some of which may be characterised as unfair competition. These include the abuse of patents. A European Commission Sector Inquiry report from 2009 said that applications to the European Patent Office (EPO) nearly doubled between 2000 and 2007.

The Commission acknowledged that the increase was partly due to 'defensive patent strategies' with the objective of 'delaying or blocking entry of generic medicines'. This included the use of patent clusters or thickets where multiple applications were filed around a single product in order to confuse actual current patent status.

We are concerned that the use of patent, or similar extensions of exclusivity, by legislators to drive industry behaviour can backfire. An example is the so-called “paediatric extension” which grants six months additional exclusivity in return for carrying out a paediatric investigation plan. These additional periods of exclusivity can cost the NHS enormous amounts of money when the actual number of new beneficiaries may be small in comparison and the research relatively low-cost.

We believe it is morally right that paediatric uses of medicines should be researched and licensed. We do not object to there being a financial incentive, if one is needed, to encourage companies to do this work. However, it just seems that high returns on such comparatively low investment are beyond all reasonable scale and proportionality.

Sustainability

Comparatively high levels of use of generic medicines within the NHS result in very significant savings to the NHS drugs bill. Without those savings, even in normal economic times, the drugs budget could become unsustainable.

Generic prescribing has grown substantially over the past 40 years, from less than one in five prescriptions issued in the mid-1970s to more than 80 per cent in recent years.

Reports by academics, competition authorities, parliaments and independent commentators establish a range of parameters that should be met to support a sustainable generic industry that makes the maximum societal contribution.

These include:

• The long-term sustainability of the generic medicines sector relies on fair prices and a level playing field, particularly in competition with branded medicines, including originators.

• A successful generic medicines policy requires both supply-side measures relating to pricing and reimbursement, and demand side incentives for physicians, pharmacists and patients.

• Significant volumes of generics and multiple suppliers are needed to ensure the maximum benefits for the NHS and patients.

• The generic medicines industry has to compete on a global scale, which includes competition from manufacturers with facilities outside of Europe. This means that it is important that policies encourage manufacture in Europe.

IQVIA data confirms that the average manufacturers selling price in the UK is the lowest in Europe and the US. This in turn benefits the NHS. However in a global market place, pricing needs to be sustainable to support a competitive and healthy supply of generic medicines to the UK in the future. We need to be careful that continuous, increasing pressure on prices in the UK does not reach a tipping point whereby supplying the UK ahead of other international markets may not considered competitive.

MHRA performance

The UK's medicines regulator 'the MHRA' rightly has a strong and positive reputation amongst its peers in the EU for its contribution and scientific expertise. Indeed, it delivers the largest share of the work in reviewing applications for pan-European marketing authorisations, of which the generic sector is the biggest user.

In the key area of new product registrations, BGMA has been closely surveying MHRA performance year on year and identifying areas requiring improvement, for discussion with the regulator. This has resulted in major improvement in the time taken for new generic medicines to be registered in the UK. This is greatly assisting the predictable timely availability of generic medicines for patients, healthcare professionals and has also resulted in NHS cost savings.

In other areas of regulation, such as changes to existing approved medicines and transferring licences, there is still a need for MHRA to focus and improve, particularly on the time taken to reach decisions.

With the increasing weight of new legislation coming from Europe, the BGMA continues to work closely with MHRA to ensure its drafting and UK implementation is well managed, and minimises red tape and over regulation. This safeguards the sustainability of the NHS, so that affordable generic medicines are quickly available to patients, allowing the NHS to afford other treatments and expensive innovative medicines for unmet clinical needs.

Better Patent Regulation

The volume of patent applications has increased substantially in the past decade, with a proportion of those apparently aimed at deterring generic competition.

Given the volume and unnecessary complexity of some patent clusters - which in certain examples have totalled nearly 1,300 patent applications around a single molecule - it is extremely difficult for generic manufacturers, particularly SMEs, to be confident they would not be in legal breach by launching their product. These practices limit competition and the prospect of lower medicine prices.

We are very concerned that the issue of these type of weak patents - those which don't fully meet accepted criteria - may be aimed at delaying generic competition.

It is crucial that competition authorities ensure that the operation of markets reverts to what was originally intended: that originators receive long periods of market monopoly on their products during the patent term so that they can recoup their research investment, followed by the immediate onset of generic competition to make medicines affordable and to promote true innovation.

Biosimilars

Biological medicines including biosimilar medicines are highly complex, protein based medicines, made or derived from living organisms typically using recombinant DNA technology. Proteins are usually much bigger in size than medicines produced by chemical synthesis and have a higher complexity and variability than small chemical compounds. They can be tailor made so they bind to specific targets in the body.

Biosimilar medicines are biological medicines that have been developed to be highly similar and clinically equivalent to an existing biological medicine and are marketed after the expiry of the patent on the originator or reference biologic.

Biosimilar medicines are comparable to their reference product as they have demonstrated no clinically meaningful differences in safety, efficacy, quality, structural characteristics and biological activity compared to that of the reference biologic.

The 12 months of 2018 were another period of significant progress for biosimilar medicines in the UK.

October saw the patent expiry of Adalimumab, the world’s top selling prescription medicine, which is expected to make the single biggest contribution to the NHS objective of saving in the order of £200 million to £300 million per year by 2021 from biosimilar medicines.

Elsewhere, and building on the experience gained with other recent biosimilar introductions, the NHS is now in a strong position to make the most of the savings opportunity delivered via competition. From a position of just a few years ago where the UK lagged behind other European countries, it is now a pre-eminent market for take up of biosimilars. That momentum mustn’t be allowed to stall or slow.

Real-world experience is among an array of factors which has been key to greater adoption and understanding to the point now where we are seeing very high levels of biosimilar usage. It is particularly important that the rapid introduction and take up of the opportunities from new biosimilar medicines is consistent across the NHS. To help achieve that, the Regional Medicines Optimisation Committees (RMOCs) have had biosimilars high on their collective agendas. The main purpose of the four RMOCs of NHS England is working together as a single system to avoid unnecessary variations in the best use of medicines.

Alongside the budget savings to the NHS from using biosimilars is the equally important benefit of freeing up resources so that more patients can have access to biological medicines and the significant health improvement benefits they can provide.

There is emerging data that when biosimilar introduction takes place, and leads to a reduction of 50% in price it also delivers a 50% increase in the number of patients that can be treated. The higher relative cost of biological medicines both in R&D and manufacturing has tended to place constraints on access and routine use. Therefore, the availability of interchangeable biosimilar medicines gives an opportunity for prescribers to revisit patient treatment pathways and the group of people considered suitable for biological treatments to be widened.

Further information on biosimilar medicines is available at the British Biosimilars Associaition website www.britishbiosimilars.co.uk .

Falsified Medicines Directive

Counterfeiting of medicines is a serious criminal act that puts people's lives at risk and is often part of organised crime. A counterfeit medicine can only reach a patient through community pharmacies if someone in the legitimate supply chain has done business with a criminal. So the most effective way of preventing counterfeiting of medicines is to ensure the integrity of the medicines supply chain through all parties doing business with certified partners only and exercising appropriate levels of due diligence.

Technical features as being proposed by the European Commission (such as mass serialisation, seals, or other similar features) do not stop criminal behaviour such as counterfeiting. They can only be seen as secondary lines of defence potentially helping to trace identified counterfeit medicines, and may give a false sense of security. They should therefore only be applied compulsorily to products at high risk of counterfeiting as required by European legislation and where they could be cost-effective.

Unsurprisingly, counterfeiters focus their efforts on high priced branded products and not generics. Though we are not complacent, we note that no counterfeit generic medicine has been discovered in the European Union.

Industry NHS guidance

We work with the NHS to develop guidance that will ensure a more efficient NHS across the UK, whether this is on helping to resolve situations when a supplier is out of stock, or to ensure that all parties are aware of their rights and responsibilities when the NHS is developing new care and pharmacy models.

Standardised management of off-contract claims guidance:

Where a contracted supplier is out of stock and it cannot arrange for an alternative supply to be provided, an NHS trust or health board may charge for the difference between the contract price and what it paid for the replacement stock.

BGMA and ABPI have worked with both the NHS and NHS Scotland to develop practical guidance for English hospital trusts and Scottish boards to help hospitals efficiently make claims when off-patent medicines are out of stock; and for suppliers to process claims efficiently. This saves time and money for both hospitals and suppliers. In some cases, following the guidance may enable medicines to be located in the supply chain so as to resolve out of stock situations. The guidance documents applying to both England and Scotland can be located here: (England) / (Scotland).

Guidance around third party pharmacy provider arrangements:

The Department of Health has issued guidance to NHS trusts about what they need to consider and put in place when establishing and running agreements with third party pharmacy providers to operate hospital outpatient dispensing or homecare services.

The DH guidance outlines that NHS trusts must request and receive written permission from contracted suppliers before sharing confidential pricing data with third party pharmacy providers; and that permission should not be assumed. The guidance goes onto list the rights and responsibilities of trusts, third party pharmacy providers and suppliers. This includes third party pharmacy providers separating their hospital and primary care operations and being able to demonstrate this; as well as reporting accurate dispensing data to CMU, thereby supporting future forecasting used for medicines tenders. The DH guidance can be located here.